We Want Them Pure and We Want Them Dirty: Celebrity Worship and Abuse

"I know I believe in nothing, but it is my nothing." — Richey Edwards, Manic Street Preachers

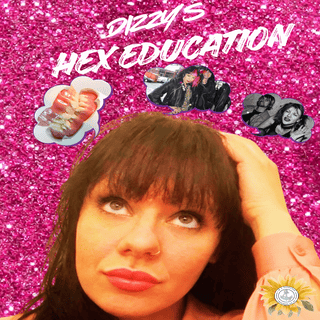

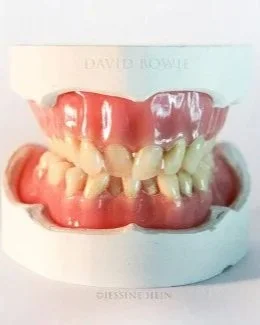

I worshipped David Bowie because his strange looks and wonky teeth made me feel better about my own. At thirteen, wonky-toothed and awkward, I found salvation in Aladdin Sane's jagged grin, in the way he wore his imperfections like armour. Here was proof that you didn't need symmetry to be extraordinary. That oddness could be power. Then I discovered late Bowie (sleek, polished, teeth fixed) and it opened a wound I didn't know how to name. The man who taught me that difference was beautiful had erased his own difference.

But that betrayal was nothing. The real wound came later, scrolling through blind items on gossip sites at 2am, the kind that don't name names but everyone knows. Lori Maddox, who claims she lost her virginity to Bowie at fourteen. Sable Starr, linked to him when she was barely past childhood. The 1970s rock scene treated teenage girls like backstage amenities. The man whose art cracked me open at my most vulnerable had allegedly cracked open girls even younger. Girls who couldn't consent. Girls who were groomed by a culture that called it liberation.

My dissertation was on abnormal sexual psychology. I spent years studying what we'd rather call evil than understand. "Monster" is easier than "human with a specific set of psychological, neurological, and environmental factors that led to harmful behaviour." Evil ends the conversation. Understanding begins prevention. Then Bowie stopped being theoretical and became personal. All that research became the lens through which I had to examine my own complicity.

"Motown junk, a lifetime of slavery / Songs of love echo underclass betrayal." — Manic Street Preachers, "Motown Junk"

I was a hair metal teenager. I saw the groupie culture firsthand. Girls waiting outside venues, some of them barely fifteen, competing for access to men twice their age. I'd been taught it was glamorous, that these girls were lucky. That this was what rock and roll looked like. Almost Famous is still one of my favourite films. Penny Lane, the band-aid, the girl who insists she's not a groupie but "a muse." The film is tender, nostalgic, and beautiful. It's also about a fifteen-year-old girl being passed between adult men like currency. Cameron Crowe, who lived it, who was the teenage journalist, frames it as romance. As a coming-of-age. As the price of proximity to genius.

"The only true currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with someone else when you're uncool." — Lester Bangs, Almost Famous

What does this mean? It means I was complicit. I watched that film at fourteen and wanted to be Penny Lane. I saw the girls outside the venues and felt jealous, not concerned. That the culture taught me to view access to male artists as an aspiration, not exploitation. That I learned to see myself through the male gaze before I'd even developed one of my own. That when I think about those girls now, I feel sick. Not just for them, but for the version of me that envied them. Every time I didn't question why grown men needed teenage girls to validate their genius.

“They need your innocence/ to steal vacant love and to destroy/ your beauty and virginity used like toys” - Manic Street Preachers, Little Baby Nothing.

Here's the contradiction: we expect artists to be morally superior. We demand they have the correct opinions on Palestine, trans rights, and climate change. We expect them to be activists, educators, and role models. But we also demand the rock and roll myth. The excess. The danger. The transgression. We want them pure, and we want them dirty. Politically righteous and hotel-room-destroying. We're setting them up to fail. Or we're setting ourselves up for heartbreak, building altars to people we've decided are better than us, then acting shocked when they're just as broken. Maybe that's the point. Maybe we need them to fail so we can express our disgust and feel morally superior for five minutes before we find the next one to worship.

Richey Edwards of the Manic Street Preachers carved "4 REAL" into his arm with a razor blade in front of a journalist. He wrote about hypocrisy, about the impossibility of living ethically under capitalism, about how we're all complicit in systems we claim to oppose. He disappeared in 1995, but his words remain: the uncomfortable truth that we can know something is wrong and still participate. That believing in nothing might be more honest than performing belief whilst changing nothing.

That's where I live now. In that nothing. In the space between knowing Bowie allegedly slept with children and still feeling my chest tighten when "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" comes on. Between understanding the power dynamics and still remembering what it felt like to be twenty and sleeping with an older artist, convinced it was my choice, my desire, my agency. It was. And it wasn't. Both things are true.

“I can see that you're 15 years old/ No, I don't want your ID/And I can see that you're so far from home” - Rolling Stones, Stray Cat Blues

The blind items keep coming. Brand New's Jesse Lacey admitted to "sexual conversations" with underage fans. PWR BTTM's Ben Hopkins, allegations of sexual assault that killed the band overnight. The Burger Records implosion when dozens of women came forward about The Buttertones, The Growlers, SWMRS. Instagram accounts like @lured_by_burger_records became confessionals, a Greek chorus of girls saying "me too, him too, them too."

I read every single one. I know their patterns by heart now. The way the stories always start with "I was a huge fan." The way they describe feeling special, chosen. The way they only realise years later that they were one of many. The way their voices shake even through text, even through the anonymity of a pseudonym, even through the years of therapy it took to name what happened to them.

Lostprophets' Ian Watkins, whose crimes were so heinous I still can't type the details without my hands shaking. The court documents are public record. I've read them. I wish I hadn't. Marilyn Manson, with allegations from Evan Rachel Wood and at least fifteen other women detailing years of abuse so systematic it had a methodology. Red Hot Chili Peppers' Anthony Kiedis, who wrote in his own autobiography Scar Tissue about having sex with a fourteen-year-old girl he met outside a liquor store, about taking her virginity, about continuing the relationship even after finding out her age. He wrote it. Published it. Promoted it on talk shows. No one cared. The book was a bestseller. The Chili Peppers still headline festivals. "Under the Bridge" still plays at every wedding, every road trip, every moment we need to feel something.

"She was just seventeen, you know what I mean." — The Beatles, "I Saw Her Standing There"

But people are happy to indulge in the misogyny of boycotting Courtney Love for "murdering" Kurt Cobain with less evidence than exists in Kiedis's own published confession. Love has been vilified for decades based on conspiracy theories and the cultural inability to accept that a woman could be talented, difficult, and grieving simultaneously. We'll destroy a woman on rumour whilst streaming a man's confession. We'll call her crazy, attention-seeking, a bad mother. We'll analyse her every word, her every outfit, her every public appearance for signs of guilt. Meanwhile, Kiedis gets a pass because he's "rock and roll." Because boys will be boys. Because genius excuses everything.

"Young girl, get out of my mind / My love for you is way out of line." — Gary Puckett & The Union Gap, "Young Girl"

Then there are the others. The ones where there are only whispers. Blind items that never get confirmed. Reddit threads. Twitter callouts. No hard proof. What do I do with them? I know the statistics. False allegations are rare, 2-8%, the same rate as other crimes. Which means the whispers are probably true. But "probably" isn't certainty, and I've built my entire moral framework on believing survivors. So when no survivors come forward, just rumour, just that sick feeling in my stomach when I see the name, what then?

Do I stop listening on a hunch? Do I wait for proof that might never come because the girls are too scared, too traumatised, too aware that no one will believe them anyway? Do I keep streaming whilst feeling complicit? I don't know. And that not-knowing feels like cowardice. It feels like I'm waiting for permission to keep enjoying the art, waiting for someone to tell me it's okay, that I'm still a good feminist, still a good person. But no one can give me that permission. There is no ethical consumption under this system. There is no clean way to love art made by predators. There's just the choice to look at it or look away.

"I'm a back door man / The men don't know but the little girls understand." — The Doors, "Back Door Man"

At what point does it become the right thing, the feminist thing, to cancel someone? I've been in relationships with power imbalances I couldn't see at the time. I know what it feels like to mistake access for intimacy, to confuse admiration with desire. I was twenty when I slept with an older artist whose work I'd loved since I was a teen. Legal. Consensual. I sought him out. And still, looking back, I can see the power imbalance I couldn't feel then. The way he knew I'd say yes before I did. The way my desire was shaped by his mythology before we ever met. The way he collected young women who loved his work, the way we all thought we were special, the way we only found out about each other years later when we'd all stopped being young enough to interest him.

So where's the line? If a twenty-five-year-old musician sleeps with an eighteen-year-old fan, is that abuse or is that legal consent complicated by admiration? If a thirty-something rock star has a relationship with a twenty-year-old who sought him out, where's the line? I don't know. But I know the power imbalance is real, even when both people want it. Especially then. I know that wanting something doesn't mean you weren't manipulated into wanting it. I know that my twenty-year-old self would be furious at me for calling it a power imbalance. And I know that's exactly the problem.

"Girls, Girls, Girls / Long legs and burgundy lips / Girls, Girls, Girls / Dancin' down on Sunset Strip." — Mötley Crüe, "Girls, Girls, Girls"

Led Zeppelin with Maddox, whom Jimmy Page kept essentially captive in his house for years. She was fourteen. He was thirty. The Rolling Stones' Bill Wyman, who started a relationship with Mandy Smith when she was thirteen, married her at eighteen, divorced her at twenty-one. He was forty-seven when they met. Steven Tyler, who became the legal guardian of a sixteen-year-old girl, Julia Holcomb, so he could take her on tour and, by his own admission, have sex with her. He was twenty-five. These weren't secrets. They were mythology. The culture didn't just permit it. It celebrated it as rock and roll excess, as the spoils of genius. As the price girls paid for proximity to greatness.

"Brown sugar, how come you taste so good?" — The Rolling Stones, "Brown Sugar"

And we bought it. I bought it. I watched The Song Remains the Same and thought Jimmy Page was a guitar god. I listened to "Wild Horses" and felt something tender. I sang along to "Dream On" without thinking about whose dream was being destroyed. The music worked. The music still works. That's the unbearable part. The art is good. The art moved me. The art changed me. And knowing what I know now doesn't make it stop working.

It's not just rock and roll. I adore Sartre, Wilde, Lord Byron. Sartre, who treated Simone de Beauvoir as his intellectual equal whilst sleeping with her students, some barely adults, creating a pipeline of young women for his consumption. Oscar Wilde, imprisoned for his sexuality, a victim of Victorian morality, who also had relationships with young rent boys, some as young as sixteen. Lord Byron, the Romantic poet whose affairs with teenage girls (including Claire Clairmont at seventeen) were part of his mythology, who abandoned his illegitimate daughter Allegra to die in a convent at five years old.

"There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all." — Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

But somehow it's more accepted in literature. We call Byron's behaviour "Byronic." We frame Sartre's exploitation as philosophical experimentation with relationship structures. We separate Wilde's victimhood from his predation. The art world has always had a higher tolerance for "complexity" when it comes to male genius. Could I burn Nausea? No. Even if I did, it's woven into my psyche. Sartre's existentialism shaped how I understand alienation, authenticity, and bad faith. His philosophy gave me language for the nausea I feel now, reading about his behaviour. The irony isn't lost on me.

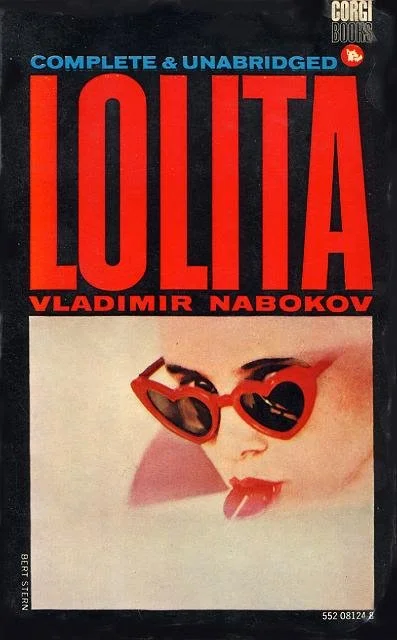

"Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta." — Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

Nabokov's Lolita is a masterpiece about a paedophile. It's written so beautifully that you almost forget Humbert Humbert is a monster. That's the point. That's the horror. The novel is a critique of our willingness to be seduced by beautiful language, to forgive the unforgivable when it's aesthetically pleasing. But how many readers missed that? How many saw it as a tragic love story? How many rock stars saw it as a roadmap?

"I looked and looked at her, and I knew, as clearly as I know that I will die, that I loved her more than anything I had ever seen or imagined on earth." — Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

That's Humbert Humbert speaking. A paedophile describing his obsession with a twelve-year-old. And it's beautiful. That's the problem. The art is beautiful. The philosophy is profound. The music works. And I can't unknow what they've taught me, can't unlearn the ways they've shaped my thinking, my writing, my understanding of the world.

"Go on, take everything / Take everything, I want you to." — Hole, "Violet"

Power without accountability doesn't corrupt. It reveals. Shows you what was always there, waiting for permission. Industries with high gender imbalances and low regulation have higher rates of sexual misconduct. Celebrity status creates entitlement and immunity. The research is detailed: access plus power plus lack of consequences equals abuse. Not sometimes. Not in isolated cases. Structurally. Inevitably. Early intervention and accountability structures can reduce harm. But we don't implement any of it because understanding feels like forgiving. Because calling someone a monster is easier than asking what made them one. Because prevention is less satisfying than punishment. Because we'd rather destroy one man's career than examine the industry that created him and will create the next one and the next one and the next one.

"Squeeze my lemon 'til the juice runs down my leg." — Led Zeppelin, "The Lemon Song"

Here's the truth: I still listen to Bowie. I still feel that old salvation when "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" comes on. Does that make me complicit? Does it make me a bad feminist? A bad survivor? I don't know.

Because the art is already inside me. It shaped who I became. I can't unlearn what Bowie taught me about transformation, about queerness, about making art from alienation. That moment when Ziggy Stardust made me feel seen exists alongside the knowledge of what he allegedly did. Both truths live in my body. They contradict. They burn. My chest tightens when "Heroes" comes on, and I don't skip it. My hands shake slightly on the steering wheel. I sing along anyway. And I hate myself for it. And I do it anyway.

“She lost all her innocence/ She said, "I am not a feminist"" — Hole, "I Think That I would Die."

What does that mean for me, still listening? For you, still streaming the Chili Peppers whilst Courtney Love remains a punchline? For all of us, expressing our disgust on social media whilst privately keeping the songs that saved us? For everyone who's ever said "I can separate the art from the artist" whilst knowing that's impossible, that the art is made of the artist, that you can't unknow what you know?

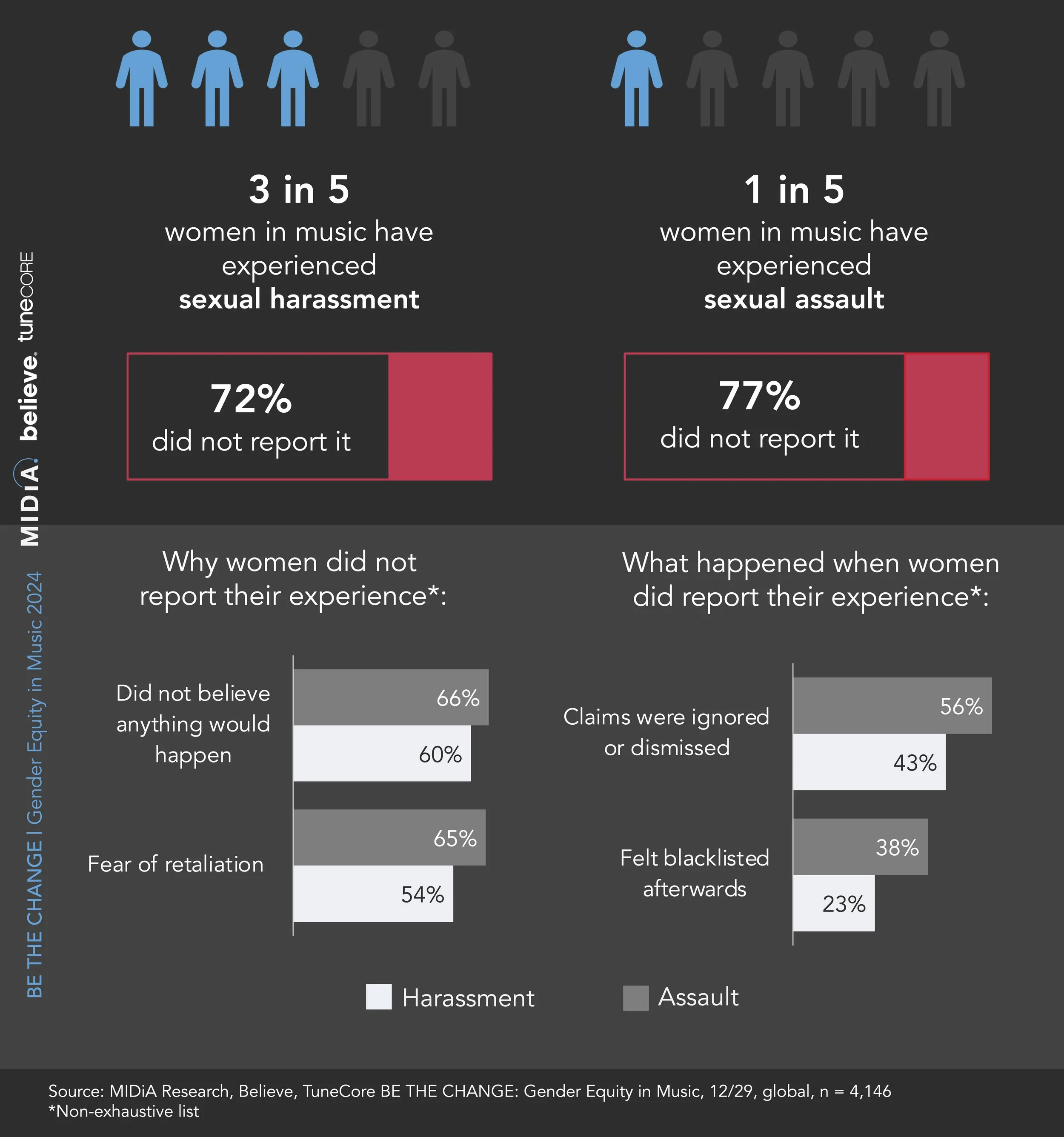

It means I'm complicit in a system that trades girls' bodies for men's genius. That cancel culture is performance. We cancel individual artists whilst the labels that protected them, the managers who facilitated access, the venues that looked away, the journalists who knew and didn't write it, the fans who heard the rumours and called the girls liars, continue untouched. R. Kelly's music gets pulled from playlists, but the record labels that profited from him for decades, that ignored the evidence, that paid off families, face no reckoning. Sixty-seven per cent of women in the music industry have experienced sexual harassment. But we'd rather destroy Courtney Love on conspiracy theories than examine why Kiedis can publish his confession and still headline Coachella.

"Culture sucks down words / Itemise loathing and feed yourself smiles." — Manic Street Preachers, "Motorcycle Emptiness"

The Burger Records collapse revealed a system where male artists saw underage fans as available, where "she knew what she was getting into" was the default defence. But we don't ask why the industry creates environments where abuse is inevitable. We don't ask what specific factors led to this behaviour and how we can prevent it. We just call it evil and move on. Because evil is easy. Evil lets us off the hook. Evil means we don't have to examine the culture that taught me to want to be Penny Lane, that taught those girls to compete for access to men who saw them as amenities, that taught all of us that this was the price of loving music. Evil means we don't have to look at ourselves.

"I was made to love magic, with a skin and a fragrance."

But Penny Lane was fifteen. Kate Hudson was twenty-one playing her, making the exploitation palatable, romantic even. The real Penny Lane - the composite of girls Cameron Crowe knew - were children. Children who believed they were special. Children who thought access to genius made them more than groupies, made them muses. Children who learned too late that muses are disposable.

I refuse to worship at altars built on girls' broken trust. But I also refuse to pretend that boycotting a playlist or festival is activism. I refuse to mistake my personal disgust for structural change. Because the truth is, I'm still complicit. You're still complicit. We're all still complicit. And performing our outrage whilst changing nothing is just another form of consumption.

"Pure or lost, spectator or crucified/ Recognised truth, acedia's blackest hole/ Junkies, winos, whores; the nation's moral suicide" — Manic Street Preachers, "Of Walking Abortion"

The uncomfortable truth is about all of us. The fans who keep falling in love despite knowing better. The industry that protects predators because they're profitable. The culture that values art more than the girls who were destroyed to make it. The teenage girl I was, watching Almost Famous and wanting to be Penny Lane, not understanding I was watching a child being exploited in soft focus. The woman I am now, still listening to Bowie, still feeling that salvation, still unable to reconcile what that means.

I still read Sartre. Still find truth in his analysis of bad faith, of self-deception, of the ways we lie to ourselves to avoid freedom's terrible responsibility. The nausea I feel reading about his exploitation of young women is the same nausea his philosophy describes - the vertigo of confronting existence without the comfort of predetermined meaning. He gave me the tools to critique him. That's the contradiction I live in.

I still quote Wilde. "We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars" is tattooed on my body. Lady Windermere's Fan, in part, got me into drama school. His words shaped my understanding of beauty in degradation, of finding transcendence in the dirt. He was right. And he was also a man who used his position to access young boys whilst being persecuted for his sexuality. Victim and predator. Both things are true simultaneously. The art remains brilliant. The harm remains real. I can't burn the tattoo off my skin any more than I can unlearn what his words taught me about surviving ugliness with grace.

Byron's poetry shaped Romanticism, shaped how we understand passion, rebellion, the tortured artist. "She walks in beauty, like the night." Beautiful. Written by a man who abandoned his daughter to die, who seduced teenagers, who built his mythology on the bodies of girls who believed his words. The Byronic hero - dark, brooding, irresistible - became the template for every rock star who came after. The direct line from Byron to Bowie is drawn in girls' blood.

"Cherry pie, you're so fine / I wanna make you mine." — Warrant, "Cherry Pie"

I still listen to Bowie. Still feel that old salvation. And I know what that costs. Not just for Lori Maddox and Sable Starr and Mandy Smith and Julia Holcomb and the fourteen-year-old girl Kiedis wrote about and the girls whose names we'll never know. They never came forward because no one would believe them, because they were told they were lucky. But for me. For the part of me that has to hold both the art that saved me and the knowledge of who created it. The part that has to live in that contradiction without resolution. My chest tightens. My hands shake. I sing along anyway.

Richey Edwards knew about this contradiction. About believing in nothing whilst still carving words into your skin. About knowing the system is broken whilst still participating in it. About hypocrisy being the only honest position left when there's no ethical way to exist under capitalism, under patriarchy, under the mythology we built on girls' backs.

"She's only seventeen (seventeen) / Daddy says she's too young, but she's old enough for me." — Winger, "Seventeen"

The question isn't whether we can separate art from the artist. The question is whether we can separate ourselves from the artist. Whether we can love the work whilst refusing to look away from the wounds. Whether we can hold the complexity without retreating into binaries. Whether we can demand structural change instead of performing individual disgust.

I don't know if I can burn Nausea. I don't know if I can delete Bowie's discography. I don't know if that would change anything. The art is already inside me. It's already shaped who I became. What I can do is refuse to let that art become a shield for abuse. Refuse to let my love for it silence the girls who paid the price. Refuse to let the mythology continue unchallenged.

"We could be heroes, just for one day." — David Bowie, "Heroes"

Or maybe I'm just making excuses for still listening to "Heroes" whilst knowing what heroes actually do to the vulnerable. Maybe there is no ethical way to love art made by predators. Maybe the discomfort is the point. Maybe sitting in that discomfort, refusing easy answers, refusing to look away - maybe that's the only honest response left.

I don't have the answer. But I'm done pretending the answer is simple.