The Algorithmic Weave: How Right-Wing Narratives Drape Modern Culture and Fashion

In the digital loom of our interconnected lives, algorithms are the unseen weavers, shaping not just what we see, but how we perceive, how we consume, and ultimately, how we exist within the cultural fabric. Far from neutral code, these digital architects subtly, yet profoundly, push narratives that intertwine politics, economics, and fashion, often with a distinctly right-wing bias, seeping into the very threads of our pop culture.

Algorithms, the computer code that works to show users content they might want or like, have also shaped how we shop. As Lascity (2021, pp.188-189) elucidates in Communicating Fashion: Clothing, Culture, and Media, algorithms mould our culture through six dimensions: patterns of inclusion, the cycle of participation, the evaluation of relevance, an implied assumption of objectivity, the entanglement of practice (response to users), and the production of calculated publics. These dimensions are not merely theoretical constructs; they are the invisible machinery that can easily be mapped onto the shifting landscapes of fashion and public consciousness.

Hemlines, History, and the Hoodwink of Nostalgia

Fashion has always been political, whether it has been used as a form of resistance or to blend into the political climate. George Taylor, in 1926, observed a deeper political and economic meaning into this relationship, noticing that women’s skirts were often shorter during times of financial prosperity, believing this could be linked to women wanting to display their silk stockings. This was also when flapper culture was thriving, which was abruptly put to a halt in 1929 with the economic crash, and women’s hemlines were longer (Humes, 2021).

However, the hemline theory can be debunked when looking at the 1980s and the stock market, as it was calm, and with the hangover of both the hippie culture and the trend of power dressing, no real correlation can be found between hemlines and the stock market (Humes, 2021). Gilbert (2017) backs up the idea that correlation cannot be found, especially due to fast fashion, which makes it particularly hard to determine patterns within fashion.

The hemline theory is overly simplified and ignores the nuance of the cultural impacts that lead to fashion trends and does not necessarily translate into modern times (Gilbert, 2017). Gilbert (2017) also argues that within modern times, nostalgia plays into fashion trends and states that in 2010, “Keep Calm and Carry On” products were linked to an imagined certainty while austerity was the reality.

Nostalgia is not only linked to fashion; it is also linked to the politics of the right. Maniaci (2023) states that this kind of nostalgia is both romanticised of a time that did not exist and a sanitised past. He also states that this nostalgia heavily leans into misogyny and classism, with the idea of tailored suits and obedient wives who are often seen in what can be considered modest dresses with longer hemlines.

The Rise of the Tradwife

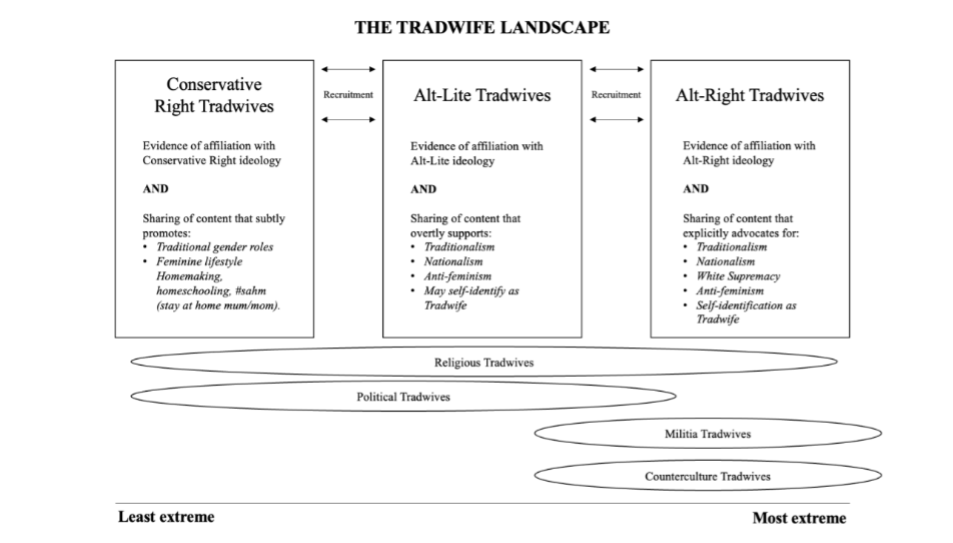

Sykes, S. (2023) The Tradwife Landscape, Global Network on Extremism and Technology.

Using nostalgia as a tool, the right-wing have commodified the idea of the tradwife to make their ideals seem a lot more palatable. Tradwives use social media to push across their ideology to appeal to both women and men by adapting and exploiting the algorithms, by adjusting their content based on the social media platform. One that is more regulated will be using dog whistles, while something less regulated such as X (formerly known as Twitter) the theoretical mask is not needed so these influencers can be more vocal about their beliefs (Sykes & Hopner, 2023).

Both Sykes and Hopner (2023) and Maniaci (2023) talk about the ideas of nostalgia and traditionalism being linked to conservatism. While Maniaci (2023) states that politicians use these ideas to “point at any group,” Sykes and Hopner (2023) express that these influencers push any ideals ranging from the “feminine lifestyle” to white supremacy through different subcategories of the tradwife culture. Sykes and Hopner (2023) go on to reveal that over time, both tradwives and their followers deepen their conservative views, and due to the lack of regulation on social media platforms, this ideology has seeped into the mainstream and offers financial opportunities to those who promote it.

Conservatism in Pop Culture and The Rebranding of Pretty Little Thing

Pretty Little Thing’s rebranding is displayed by their logo (2025)

“Wealth is what you don’t see” (Housel, 2020, p. 99). The idea of new money is considered tacky, something that is often associated with Black and Brown men and women, while generational wealth is based on classism and elitism. Both are based on systematic inequality and push the ideals of Eurocentric beauty standards (Macieira-Fielding, 2025).

With the rise of the tradwife and traditionally feminine aesthetics such as the ‘clean girl aesthetic’ indicates a backlash to either burnout or economic instability. However, through these aesthetics shows the creeping return of strict gender roles becoming popular. It shows how quickly brands, such as Pretty Little Thing, who went through their own rebranding (Fig. 3: Pretty Little Thing Logo before and after rebranding), are willing to profit from this rise of conservatism (Macieira-Fielding, 2025). As discussed before, the commodification of the tradwife, who adapts to the algorithms and can manipulate them to push their right-wing ideals, has worked to make this popular (Sykes & Hopner, 2023).

Stock (2025) supports the ideas put forward by Sykes and Hopner (2023) and Macieira-Fielding (2025), but speaks more in-depth about women’s rights and how the landscape for women is one that’s in a very precarious place globally. As of April 16, 2025, the UK Supreme Court ruled that the legal definition of a woman is based on biological sex, stating that the terms “man,” “woman,” and “sex” in the Equality Act 2010 refer to biological sex [Source: BBC News, "UK Supreme Court rules legal definition of a woman is based ... - BBC" (2025); The Lancet, "The UK Supreme Court's ruling and the rights of transgender people" (2025)]. While this ruling has significant implications, the court also clarified that transgender people still have legal protection from discrimination [Source: BBC News, "UK Supreme Court rules legal definition of a woman is based ... - BBC" (2025); Bates Wells, "UK Supreme Court Unanimously Rules Legal Definition of 'Woman' in the Equality Act 2010 is Based on Biological Sex" (2025)]. Stock (2025) goes on to express that Pretty Little Thing’s rebranding is one that is superficial and glamourises the idea of the housewife and such trends as ‘cottagecore’ are the idealisation of ‘tradition,’ but with rebranding, it also indicates how fast fashion has no identity at the core (Macieira-Fielding, 2025).

New York Magazine’s January cover for ‘The Cruel Kids Table’ (2025) New York Magazine

A further indication of how conservatism is using influencers to sway culture and fashion towards their favour is New York Magazine’s Cruel Kids’ Table. Tenbarge (2025), in the video titled “How Conservatism Infiltrated Pop Culture” (Bernstein, 2025), discusses the idea that it’s very difficult to separate influencer culture and what’s popular online and states that the Kardashians are a prime example. Ten years ago, when Obama was in power, they were supportive of the Democratic party, while also appropriating Black culture, which influenced the mainstream. Now, with this rise of ‘traditionalism,’ they have also embraced this ‘quiet luxury’ trend, while also celebrating Melania’s fashion at the inauguration for their millions of followers to see.

Conclusion

Algorithms are something that have a multifaceted influence on society, culture, and fashion. While it is something that is tailored to the users of social media, often the algorithms can be manipulated by those who know how to do so to gain followers and push their messages across. With the right-wing influencers, they have managed to do so successfully, influencing not only how people shop but fashion itself. Bernstein (2025) has argued that with these trends, the consumers are “faking the aesthetic of white supremacy and fascism,” while Tenbarge (2025), in response, also argues that “people are blindly consuming this conservative sphere uncritically.” This results in people wanting to push across an image of wealth and luxury using their muted colour palettes because it is something seen as aspirational, when the reality is the opposite, as more often than not they are wearing cheap polyester from Pretty Little Thing. To quote Stock (2025), “Fashion is resistance, every outfit is a choice.” With these trends, we are seeing the idea of faking the aesthetic for the Instagram feed to fall into favour with what’s popular with the algorithm at the current moment in time, something that contradicts the idea of ‘quiet wealth.’ This has almost become a uniform that reflects the current loss of rights in society while trying to grasp onto the idea of stability (both economically and politically), which is a life that many millennials and Gen Z have not experienced so far, and this has only become more apparent since COVID and is currently being reflected in the laws that are being passed.

A previous version of this article, was submitted as part of Ruby’s University work, it has been updated and edited to reflect the current situation.